As expected, China reported lackluster trade numbers this week, signaling a possible recession in the U.S. and more trouble for the global economy.

Chinese exports fell for the first time in three months, dropping 7.5% year-on-year to $283.5 billion. Imports dropped 4.5% to $217.7 billion.

The World Bank this week said that the global economy is in a “precarious state” and global gross domestic product growth will fall to 2.1% in 2023 and 2.4% in 2024 from 3.1% in 2022. Deputy chief economist Ayhan Kose called the current situation a “sharp, synchronized global slowdown.”

One exception is China, which is expected to grow 5.6% this year and 4.6% next year. But that growth will be animated by its internal engine, not by exports.

The reports of shipments to the world’s richest economies, trade flows that have underpinned the global economy for 20 years, were especially bleak. Exports to the U.S. dropped 18.2% to $42.5 billion. Exports to the European Union fell 6.9% to $44.6 billion. Sales of consumers goods favored by Europeans and Americans continue to plummet. Exports of high-tech products dropped 13.5% to $65.5 billion. Sales of mobile phones fell 25% to $8.3 billion. Exports of footwear declined 9.3% to $4.6 billion.

Chinese exports fell in other areas, too. Exports of agricultural products fell 7% to $8.1 billion. And it’s impacting other regions. Exports to Latin America fell 1% to $21.3 billion.

To be sure, there were some bright spots for exports. Shipments to Africa soared 13.7% to $15.9 billion. And the automotive industry continues to boom. Exports of cars increased 123.5% to $9 billion.

Exports of petroleum products increased 16% to $3.6% billion. Handbag and luggage exports rose 2.4% to $3.3 billion. Exports of steel products increased 7.9% to 8.4 million tons but fell 27.5% to $7.7 billion tons on price declines.

However, one corner of China’s trade balance sheet glowed a shining green. Since 2020, propelled by the increasing prosperity of its people, the country has asserted itself as the world’s dominant buyer of agricultural products, to the extent that it now makes sense to see China’s demand for stuff its people can eat as one of its dominant characteristics in the global economy.

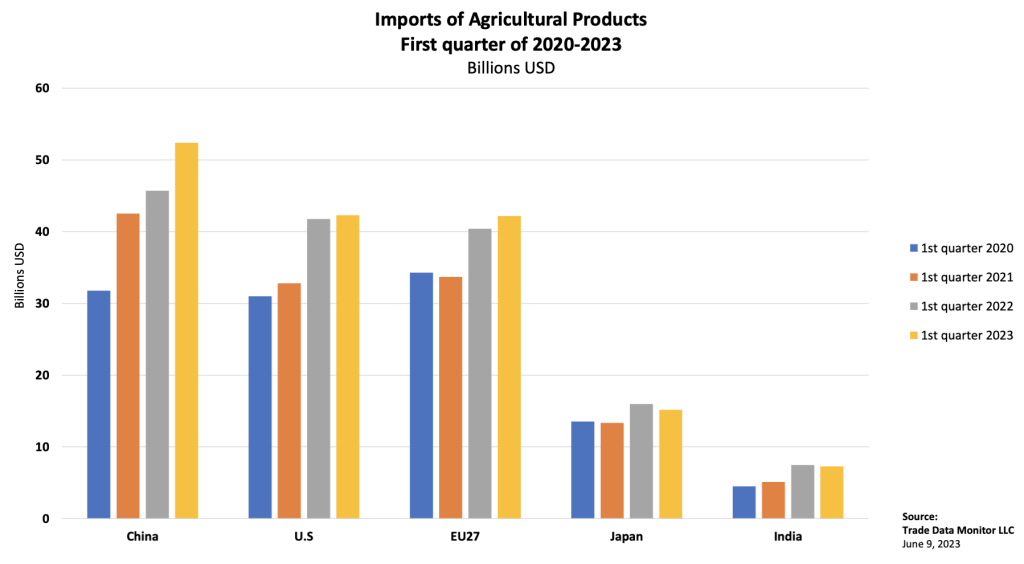

In 2020, China passed the U.S and Europe as the biggest importer of food and agricultural products, buying $146.8 billion worth of a bucket of food and agricultural products compiled by Trade Data Monitor, compared to $132.9 billion for the EU and $120.8 billion for the U.S.

In the first quarter of 2023, China imported $52.4 billion of that bucket, up 14.6% from the first quarter of 2022, while the U.S. imported $42.3 billion, up 1.3%, and the EU imported $42.2 billion, up 4.4%.

In May of 2023, Chinese imports of “agricultural product” rose 2.6% to $22.9 billion. Imports of soybeans rose 14.4% to $7.4 billion by value, and 24.3% to 12 million tons by quantity. Imports of grain increased 6.3% to $9.4 billion.

China’s appetite for food and agriculture might be what balances its trade surplus in the end. “China’s exports will remain subdued, as we anticipate the U.S. economy to enter recession,” Lloyd Chan of Oxford Economics wrote in a research note.

In non-ag sectors, imports mostly declined as sharply as exports. Imports from the U.S. declined 9.7% to $14.3 billion. From Africa, they fell 7.9% to $9.4 billion.

Two exceptions, both regarding commodity and agricultural powers: Imports from Latin America increased 9.1% to $23.1 billion, and imports from Canada rose 56.9% to $4 billion.

And China of course continues to be Russia’s main trading partner, and those trade flows increase to record highs in May. Imports from Russia increased 6.6% to $11.3 billion. Exports to Russia rose 115% to $9.3 billion.